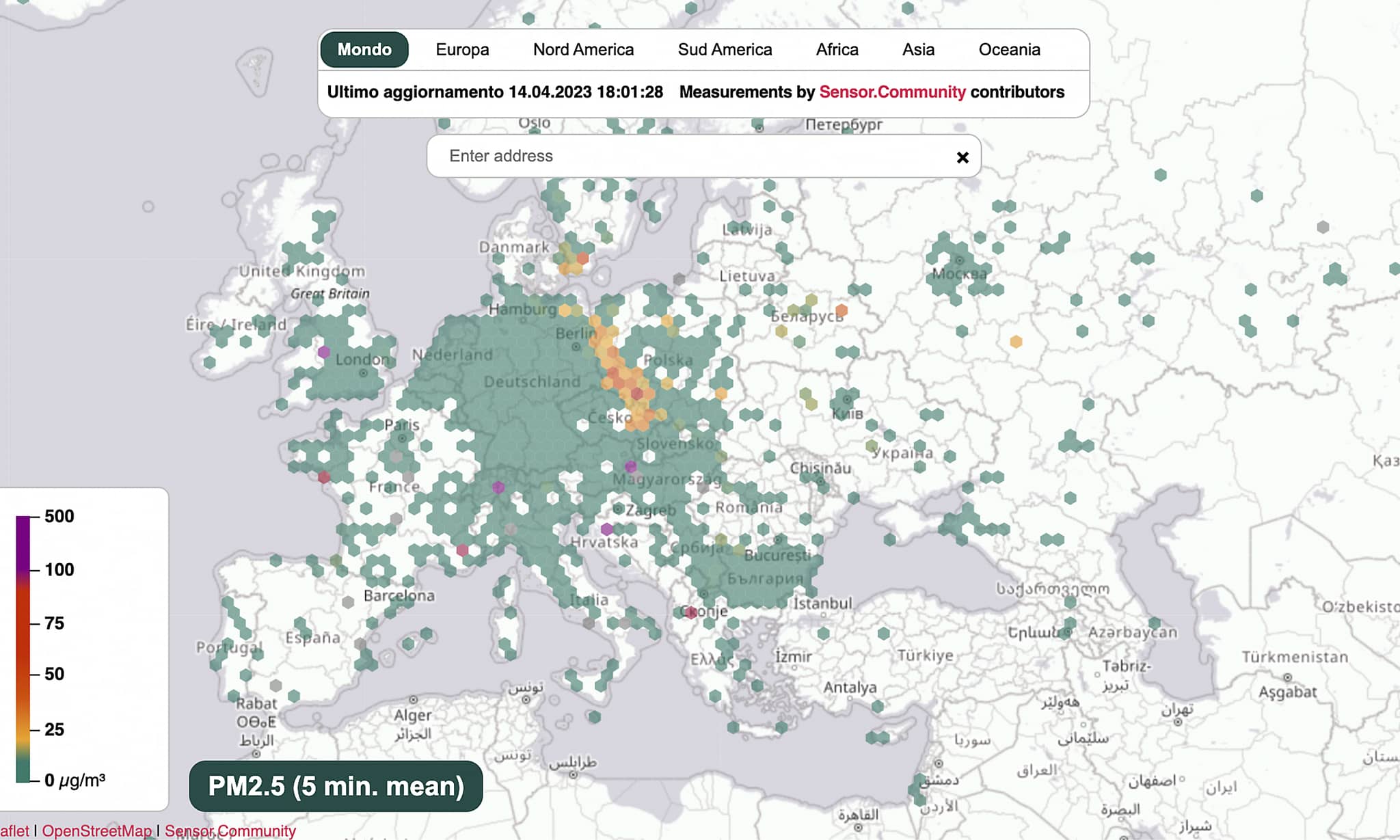

Put these sensors in the hands of citizens, and you get billions

of data from them, thanks to a

network of fourteen thousand sensor stations placed in over 70 countries. A grassroots

movement based on sharing, in full hacker spirit. We talked about it with Lukas Mocek, core

team member of the Sensor.Community platform.

Europe's air is under observation: specifically, is being watched by citizens themselves, who have taken control of the data by mounting sensor-equipped control units. The sensor is the lever of this change in perspective: an inexpensive device, easy to install anywhere, capable of detecting useful information and potentially open to future, possible new applications. When institutions decide to adopt it en masse, it will be a big step for humanity.

Every two and a half minutes, the

map gathers millions of open

and accessible data, thanks to the citizen communities that have

installed the sensor kit.

Born as a system for measuring particulate matter, the Sensor.Community project has evolved to become a grassroots movement with a global reach, with strong characteristics of shared social responsibility. From data awareness to planning concrete interventions, the step is getting shorter and shorter: the proliferation of big data makes it possible to rely on accurate assessments for any precise situation, stimulating a real and positive impact in people's lives, even for those not directly affected. We interviewed a member of the core team at the Sensor.Community: Lukas Mocek, who focuses precisely on Community Development and International Partnerships.

What is Sensor.Community, in a nutshell?

It is the global platform for environmental Open Data. Basically, a worldwide network of sensors that monitor air quality (PM 10 and PM 2.5), temperature, pressure, relative humidity, and noise pollution, then share the information on a map in a continuous stream available to all, with the ability to browse, share online, and download the history as well.

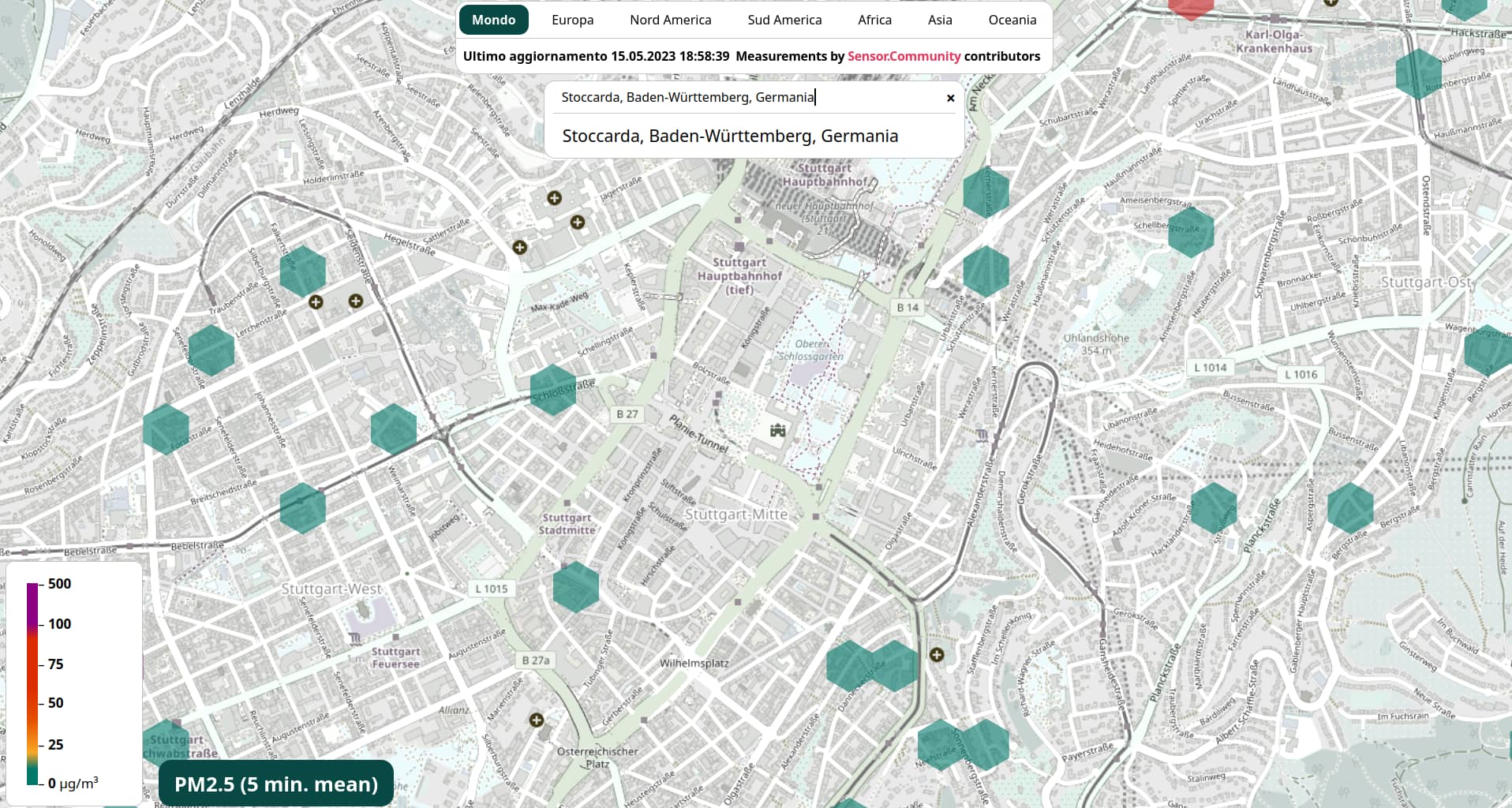

How did the project start?

By initially monitoring Stuttgart's air quality through 300 low-cost sensors. That air was said to be as polluted as Beijing's, but what did that mean in practice? Official data was either missing, out of date, or not shared by institutions. There was (and still is) no official system to help citizens gain awareness and make decisions in real time. Then a meteorologist gave an initial impetus to building fixed-installation sensors, and within a short time, the project took off in seven other countries thanks to the motivation of many volunteers, including several experienced engineers. Nowadays, our network of 14.000 sensors is distributed over five continents. With this deployed on scale combined with the experience we gained in these years, the platform has come to be ready to serve the global south accordingly.

What was your role in the birth and development of the project?

At the height of 300 sensors, I joined the team to envision the next development, glimpsing its potential and looking abroad. There were already some expressions of interest in other countries, along with volunteers ready to translate the project into their own languages. Sensor.Community soon gained an international scope, also expanding the type of measurements to other environmental data (noise and NO2).

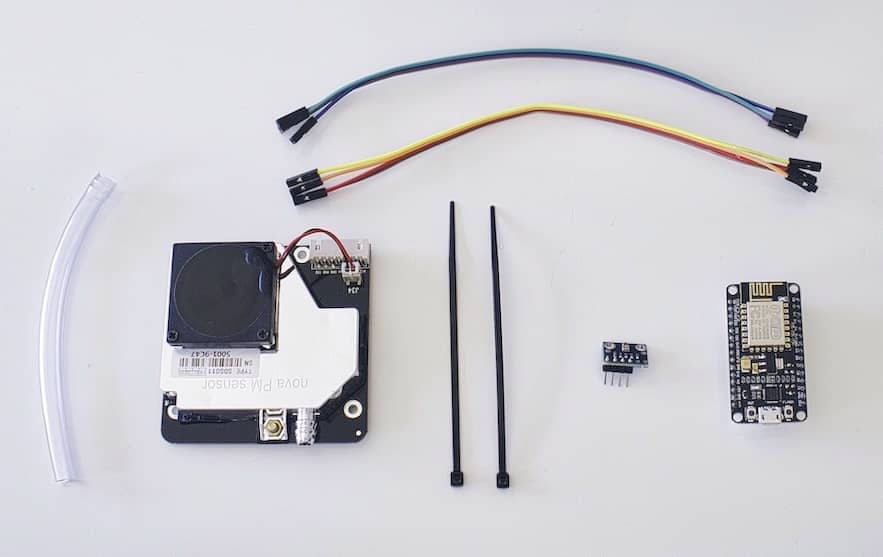

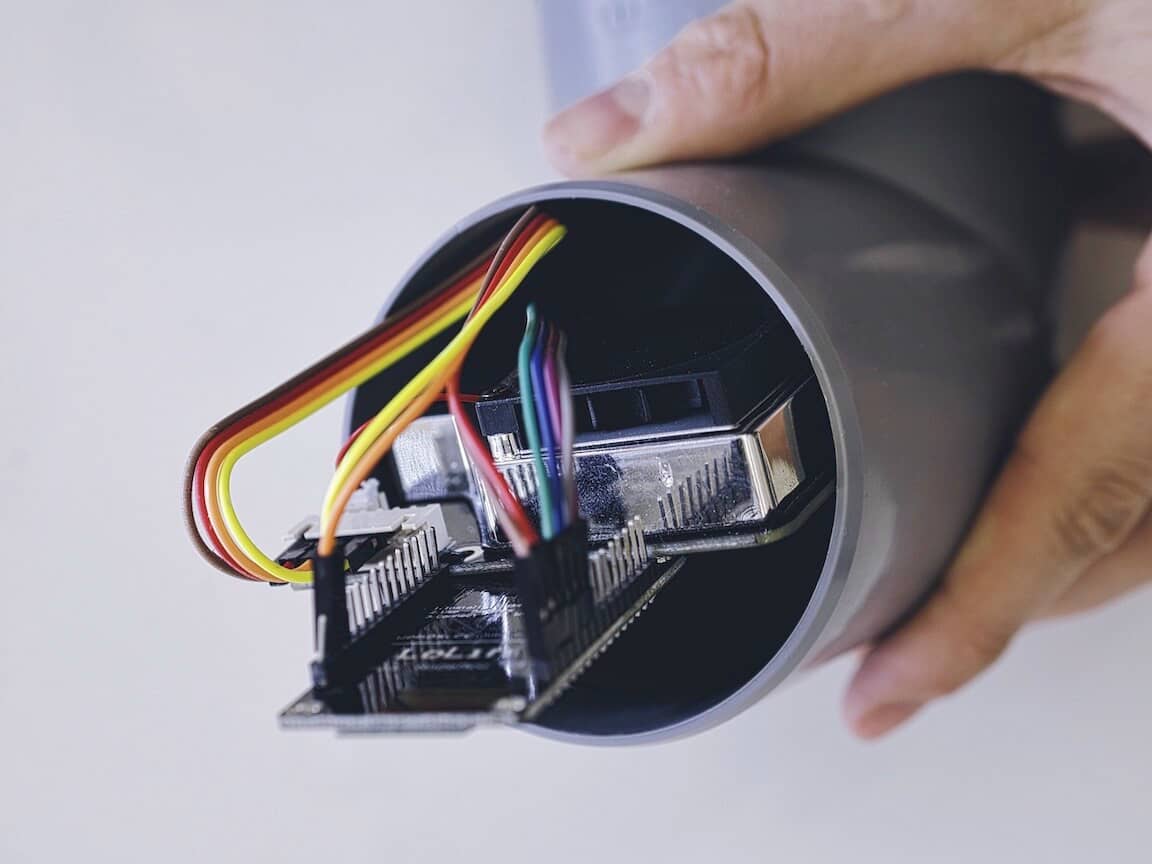

How does one join the community?

First by forming a local group among neighbors, other people who care about the environment or their family's health. Then you can purchase the complete kit or individual components to assemble, following our step-by-step guide translated into more than twenty languages. The package includes the software to operate the control unit and an installation guide. The ease of assembly and low cost are decisive factors: for example, in 2018 as many as 800 sensors were installed in Bulgaria in just a few months.

Have the institutions acknowledged the enormous potential of this data?

We have participated in several working groups of both the European Community and the United Nations, and we actively collaborate with the Ministry of Environment and Health of the Netherlands and the Environment Agency of Flanders(Belgium). At the moment, we are a complement to existing official networks and are also located in places where official measuring stations do not carry out analysis. In some cases, our collaboration with these institutions began already at the stage of sensor installation, with locations being identified from shared assessments. However, the real breakthrough would come from an official coordination agreement, aimed to avoid unnecessary delays in the fight against climate change.

To explain the growth of the community, you used the expression "feedback loop." Can you elaborate on that?

Every time you put a piece of data under the magnifying glass, you raise the level of awareness about the factor being investigated: that's what the “feedback loop” is all about. Therefore, an air quality map is actually a very efficient method to put the focus on pollution and the variables that alter a precarious balance. And from analysis one can easily move to collective action, as the number of people willing to contribute to change through creative and technological innovations also grows.

How much of a "hacker" is there in this?

Today a hacker is someone who understands how things work and aims to create something new and useful for everyone, transparently and through Open Source code, sharing the ownership of data in order to pursue innovation. We presented the Sensor.Community platform at international events dedicated to developers such as the MCH2022.org camp in the Netherlands and Fosdem in Brussels in an atmosphere of true collaboration among hackers. It is precisely from these moments of important confrontation, and as a result of feedback received from local groups, that we start to experiment with new tools and solutions. We are an active part of Open Science and Civic Tech, also we use Open Source and self-hosted tools for internal communication. And privacy is always protected, because the personal data requested is limited to the bare minimum and is neither searchable nor linked to Sensor.Community Open Data.

We began monitoring Stuttgart's air quality through 300 low-cost

sensors. Today, there are 14,000 sensors, scattered in more than 70

countries.

On balance, what do the sensors tell us about air quality?

By interpreting the data measured by the sensors, a great variability emerges; this depends on several factors, mostly related to the meteorological context. For example, wind strongly affects the results, and there can be important differences even from one neighborhood to another. With a widespread deployment of sensors, citizens will, for example, be able to decide whether to go out for a jog based on the pollution rate.

Economically, who supports the project?

The project relies on voluntary contributions and, only to a small extent, on donations received through the website. But the real capital is the result of the fourteen thousand users who decided to invest in the purchase and installation of a sensor. On balance, this is equals more than 750,000 euros. The system resembles a crowdfunding campaign and has all the prerequisites to feed itself indefinitely.